By Ben King

A blog exploring how Black culture and identity changed Britains pop culture and music throughout the 20th century.

Blog 4: The 1980s and taking a look at the impact of past influences

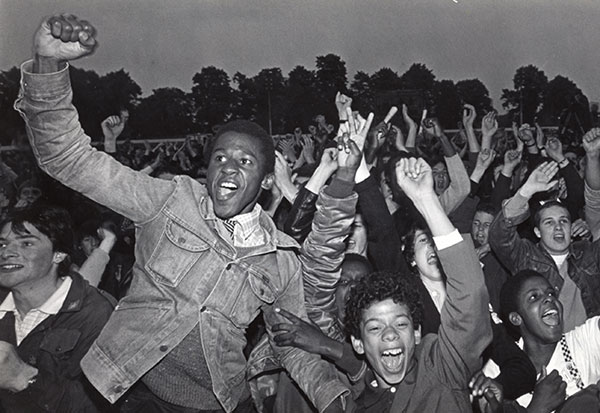

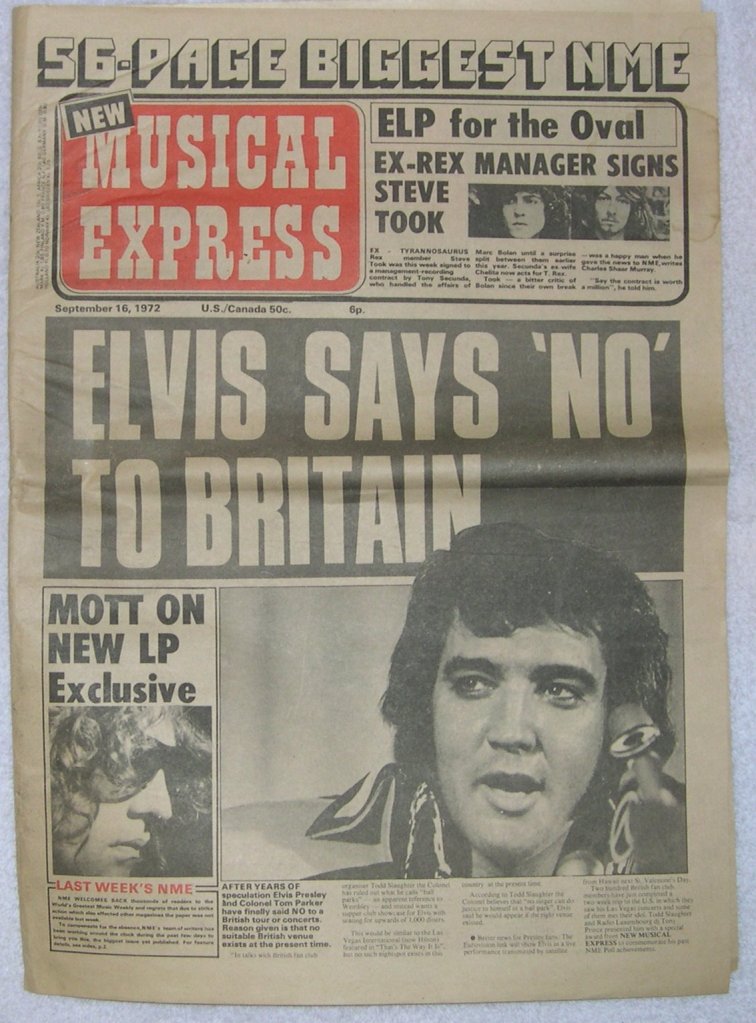

From the past few blog posts, it is pretty easy to conclude that Black identity and culture certainly made a lasting impression on Britain. However, it did not stop at the 70s. The 80s are not to be left out of our exploration into the change in Black culture and Identity in Britain. 1979 saw Margret Thatcher take the position of the prime minister of Britain, and with her, she brought hardship for a lot of the working class of the country. With high numbers of employment at the time riots ran high and with the police still in a state of racist corruption, Black people were subjected to discrimination. Matters were made worse when Margret Thatcher came out with her ‘swamped’ speech. This brought up the matter of excusing racist violence and hostility as a natural response to the threat of ‘British Culture’ posed by the commonwealth immigrants making homes in Britain.[1]

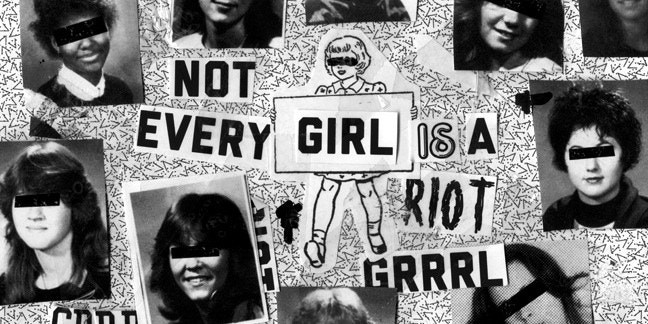

With high tensions between people of different ethnicities, aided by politics and government, came another stage in black culture, Dub poetry. Dub poetry in its simplest terms was poetry spoken with an often-radical political message, said to a reggae beat.[2]

The British government started to take a different approach to political campaigns. Specifically speaking of the conservative party’s approach with their ‘one nation’ campaign. This was brought on by the radical activities of the Brixton riot and New Cross Massacre, where it became obvious that non-white people in Britain could no longer be ignored or brushed under the mat.[3] It was the 80s that saw the first Black MPs in Britain and from there, slowly but surely equal right have started to improved, of course, there has been set back during this time and unfortunately fascism and racism can still be seen.

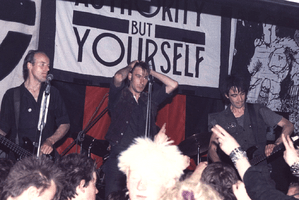

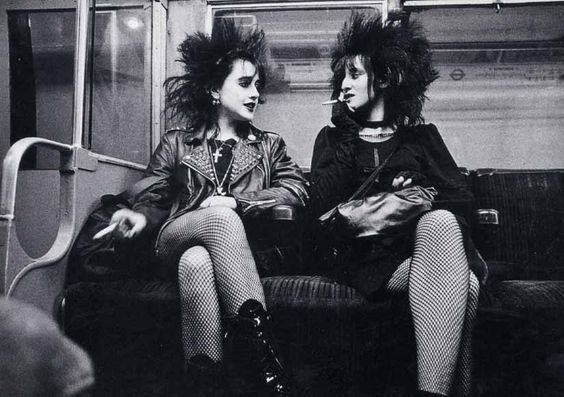

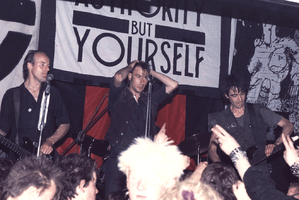

It can be said without a doubt that the music that came from a Black culture in the decades we have explored had a lasting impact on today. Examples lay in musicians such as Tom Misch, with his jazz/funk fusion, and collaborations with jazz-rap artists such as De La Soul. With politics increasingly being at the forefront of people’s minds, punk has also made a comeback with a large amount of punk having a political message of the wrongs of inequality.

[1]Stuart Jeffries, “ ‘Swamped’ and ‘riddled’: the toxic words that wreck public discourse” Last modified 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/oct/27/swamped-and-riddled-toxic-phrases-wreck-politics-immigration-michael-fallon

[2] Christian Habekost, Verbal Riddim: The Politics and Aesthetics of African-Caribbean Dub Poetry (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1993) 159.

[3] Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The cultural politics of race and nation (London: Routledge, 2002) 148.