Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/goldsmiths/detail.action?docID=4791304.

Fryer, Peter. Staying power, the history of black people in Britain. Pluto Press, 1984

Moliterno, Alessandro G. “What Riot? Punk Rock Politics, Fascism, and Rock Against Racism.” Last modified 2012, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/612/2/what-riot-punk-rock-politics-fascism-and-rock-against-racism

Panayi, Panikos. Immigration, Ethnicity, and Racism in Britain, 1815-1945. Manchester [England]: Manchester University Press, 1994.

Sivanandan, A. A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance. London: Pluto Press, 1982.

There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack’: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Hutchinson, 1987. https://www.dawsonera.com/Shibboleth.sso/Login?entityID=https://idp.goldsmiths.ac.uk/idp/shibboleth&target=https://www.dawsonera.com/depp/shibboleth/ShibbolethLogin.html?dest=https://www.dawsonera.com/abstract/9780203995075.

‘The Caribbean has long since been a region with a surfeit of labour, and consequently a region from which labour has been exported.’ [1]

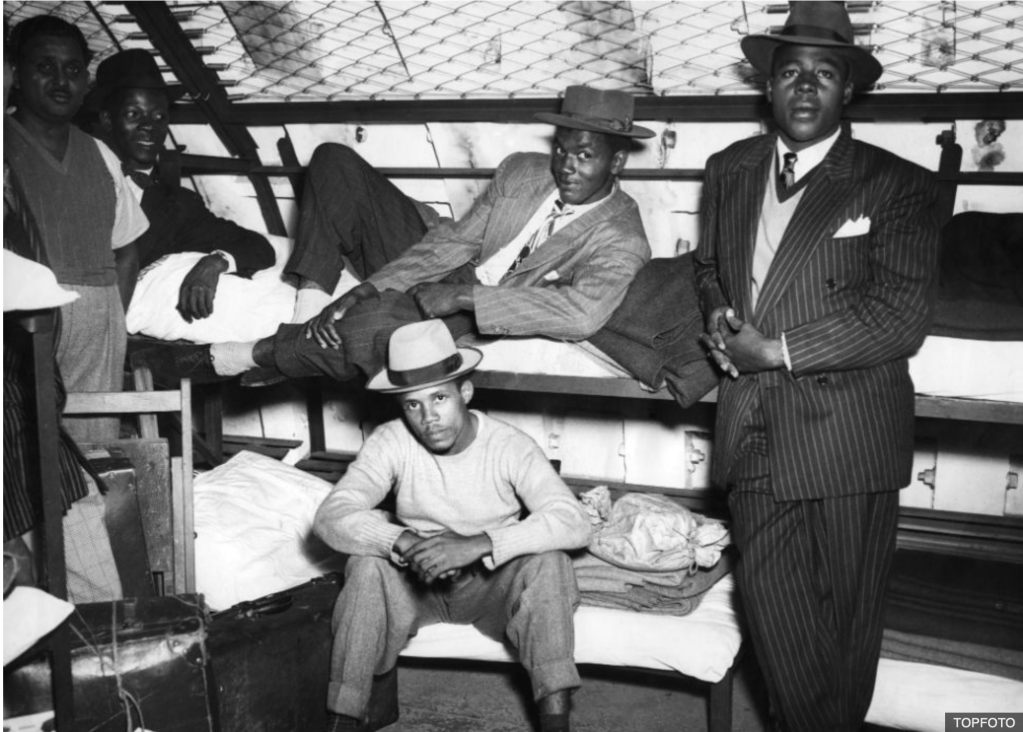

Wind rush was the largest scale of migration after world war two. There were various push and pull factors that bought people to Britain as the newly independent colonies found themselves in a state of impoverishment after years of exploitation through colonial rule from the British.[2] As well as the destruction reaped through natural disasters in Jamaica such as Hurricane Charlie. Britain, in contrast, had emerged victorious from world war two. The British economy needed rebuilding, fast. There weren’t enough British men in factories and public services and so Britain turned to its subjects overseas as they soon realised that due to its severe economic depression, places like the Caribbean could again be exploited.

As British legislation had also been updated to allow this migration, the 1948 nationality act formally giving British subjects the new status of ‘commonwealth’ citizen. People of the commonwealth had been taught to retain a sense of pride and affection for mother country of Britain. [3] However, upon arrival they were continuously alienated through overt and covert racism and continuously let down by the British government and with the popular culture of Britain. These experiences of alienation from the ‘mother country’ and severed ties to cultures back home and continued hostility from the British public led to the disillusionment the migrants experienced when stepping foot on British land, experiencing hostility and alienation from a nation which they were both a part of and had contributed to throughout history.

‘these migrants found themselves not being treated as fellow brits, but as sinister foreigners’ [4]

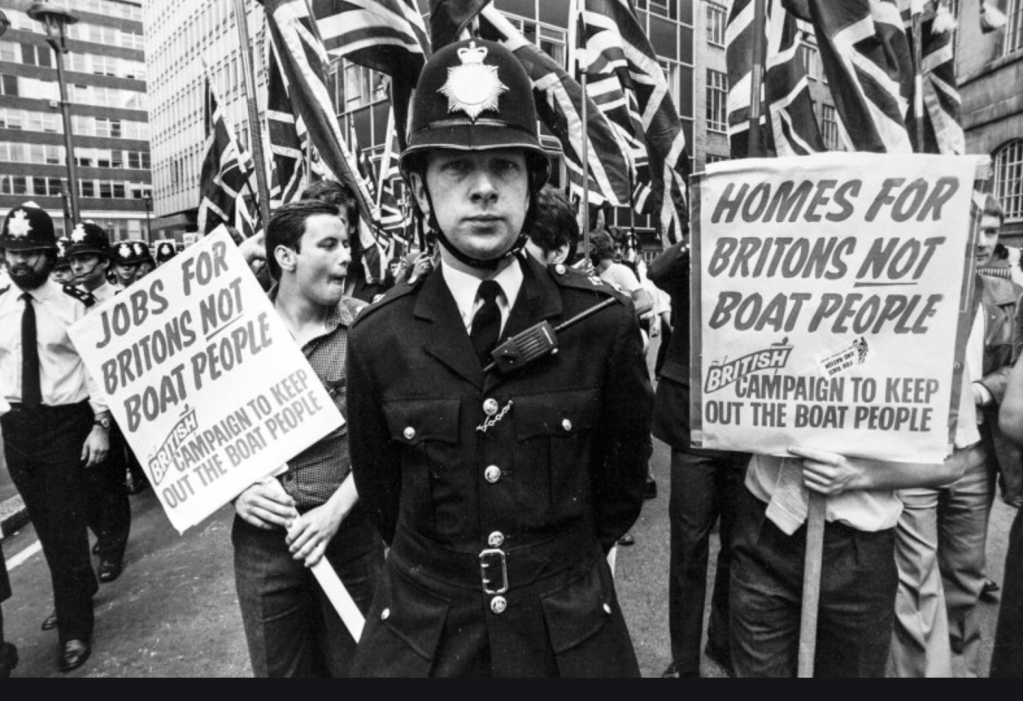

A blatant ‘demonisation of immigrant and foreigners was to become a perennial feature of public and political discourse.’ [5] Support for migrants was nowhere to be found within the systematic racism which existed in Britain and so during this time it had to come from their own local organisations and communities. Creating an environment where communities of migrants became insular and further alienated from mainstream British popular culture. The fact that Britain was completely ignorant to the cultural heritage, history, geography led immigrants a need to retain a sense of cultural identity as well as assimilating themselves into British culture. Especially by the second generation of wind rush. [6] These people had been completely cut off from the culture of their homes as their stay in Britain became more permanent and legislation prevented further migration. ‘Those Caribbean people already resident in Britain found themselves.. cut off quite literally from family and friends in Caribbean.’ [7] They therefore had to build something for themselves in the hostile landscape of Britain and music was a way in which to do this. Migrants found themselves in a state of constant resistance to British people socially assigning identities to migrants and the ‘lumping together’ of cultural heritage. [8] And so as Paul Gilroy states in his work on cultural politics of race and nation, ‘recognition of the ways in which Britons black populations are subject to particularly intense forms of disadvantage and exploitation.’ [9] There was a distinct need to express this struggle within the forms of music and art to form a collective identity against this systematic oppression.

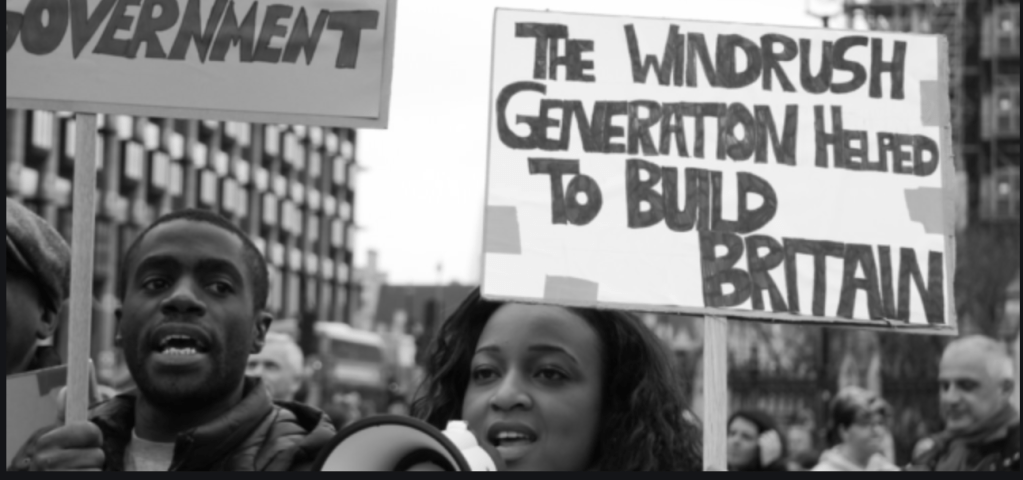

The children of Windrush sought to claim a distinctive black-british cultural identity and it began to emerge as migrants looked toward black conciousness and political movements flourishing in the States. Music was a crucial way in which black British youth could express this rejection of their discrimination. The disappointment and anger toward a government who had completely failed them and their parents before them and the lack of affinity they felt with the people of Britain. In the following posts I will explore how music was a key defining feature in this development of identity and how it transformed the punk and ska scenes over the decades.

‘Since the end of the world war millions of migrants and their offspring have helped to revitalise and transform Britain.’ [10]

[1]Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/goldsmiths/detail.action?docID=4791304. p.29

[2] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.29

[3] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.27

[4] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.32

[5] Sivanandan, A. A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance. London: Pluto Press, 1982. p.35

[6]Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain. p.32

[7] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.42

[8] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.42

[9] There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack’: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Hutchinson, 1987. https://www.dawsonera.com/Shibboleth.sso/Login?entityID=https://idp.goldsmiths.ac.uk/idp/shibboleth&target=https://www.dawsonera.com/depp/shibboleth/ShibbolethLogin.html?dest=https://www.dawsonera.com/abstract/9780203995075. P.10

[10] Panayi, Panikos. Immigration, Ethnicity, and Racism in Britain, 1815-1945. Manchester [England]: Manchester University Press, 1994.

This post will explore the ‘The role of the state as an employer and as a provider of income, and the growth of structural unemployment’ [1] and how this contributed to the sound of punk.

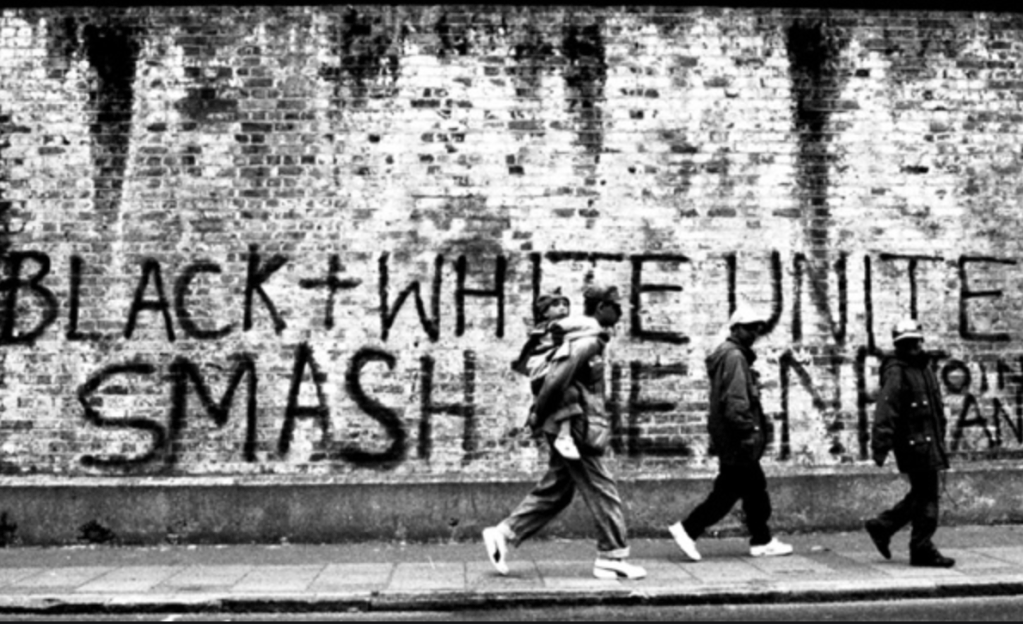

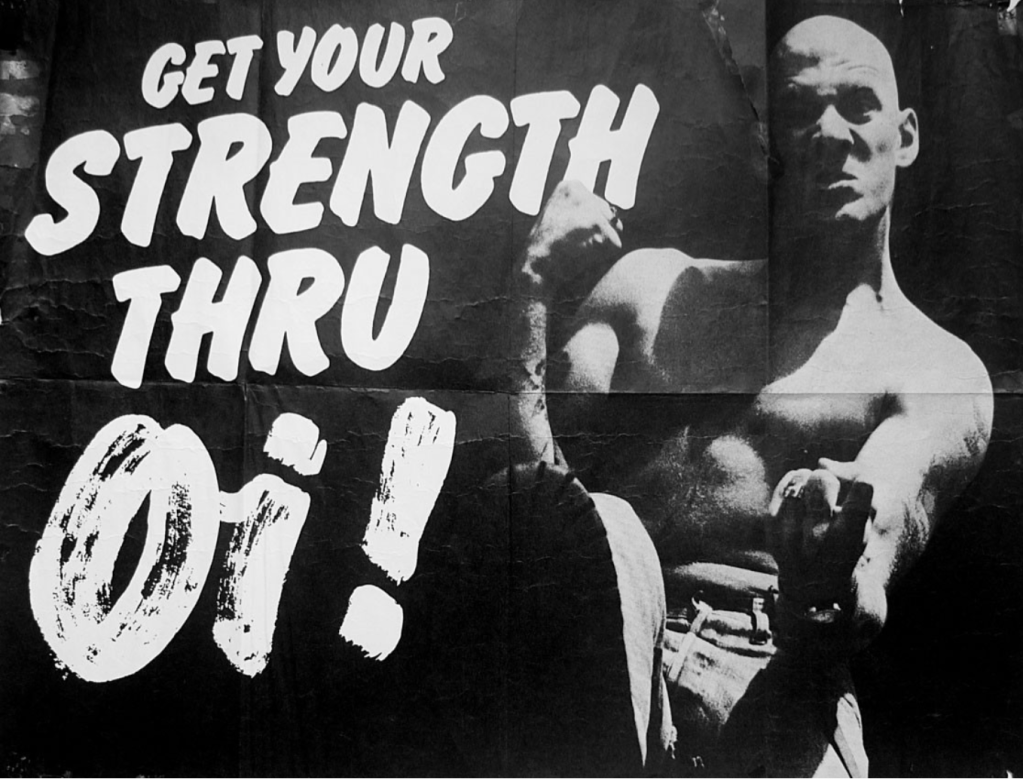

Actions throughout the course of thatchers government had an extremely negative effect within inner cities by the 1970s due to the privatisation of much of the Britains nationalised industries causing widespread factory closure and with it, many of the working class jobs which had been a meagre source of income in a time where money was extremely scarce. This contributed to the rising unemployment in the 1980s and this unemployment disproportionally affected black young men. ‘In the longer term, migrants found themselves vastly affected by the decline of manufacturing industry from the 1970’s because they initially concentrated in that type of employment.’ [2] This wave of unemployment especially in cities where school funding had been neglected, and youth who had been failed by this education system found themselves with an enormous amount of time to ‘reflect on matters of group identity.’ [3] The youth of Britain found themselves in a decade of economic stagnation and those who had became disillusioned by government neglect turned to the sound of punk to express the anger and mistrust of the white, middle class people who held the positions of such power. The punk scene offered a subculture which subverted the establishment which had done such a disservice to the working classes and particularly migrants until this point. The end of deference during the late 1960s and 70s gave a voice to those who had been oppressed by legislation and the looming lack of career opportunities. Especially the migrants who had been continuously demonised by the media and on the streets of England. the emergence of reggae being ever more popular within the sounds of punk with its affinity to ska provided a respite to the overt racism found everywhere in England. Where everywhere else the colour of someones skin seemed to dictate how you were treated in so many parts of life, housing, education, socially and within employment. This discrimination led to an increase in political activism amongst black and asian workers who found a voice and identity in the numbers flocking toward the skinhead and punk sound and message. With left-leaning tendencies offering a voice to people who had found they were being overshadowed by an out of touch and hostile government.

British working class youths fought to define and redefine their identities, their styles, in response to black immigration and culture’ [4]

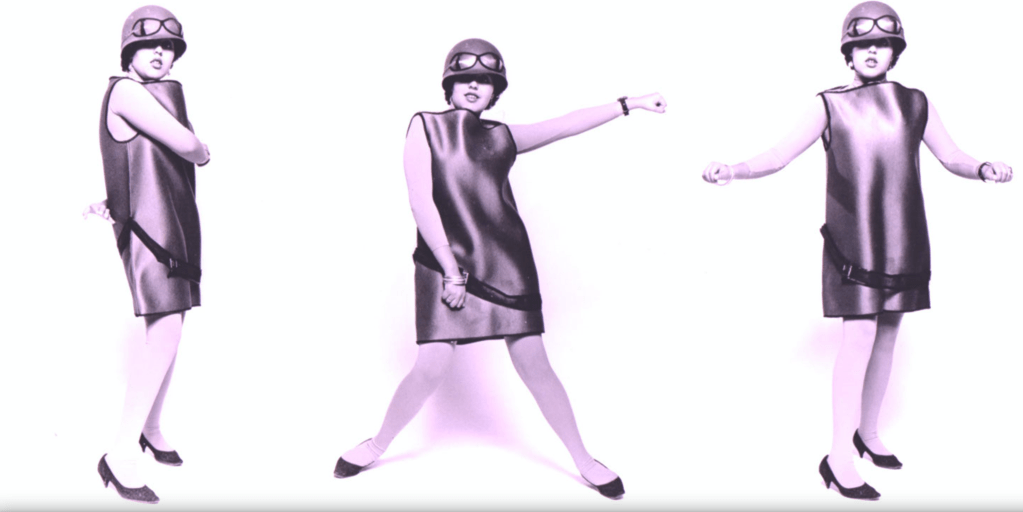

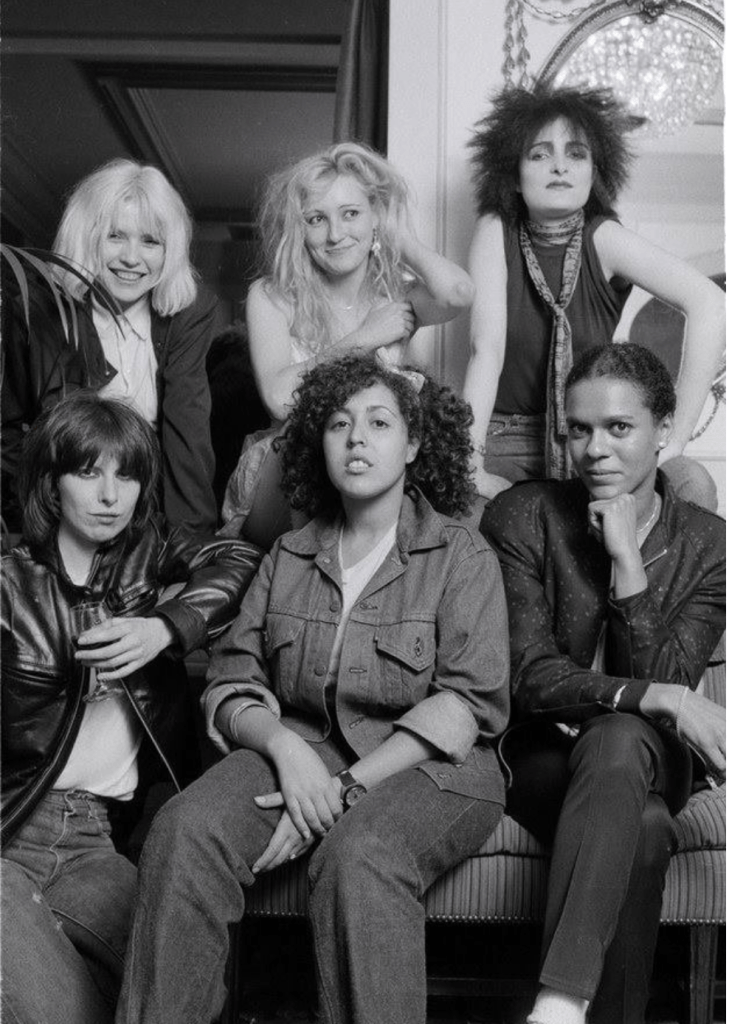

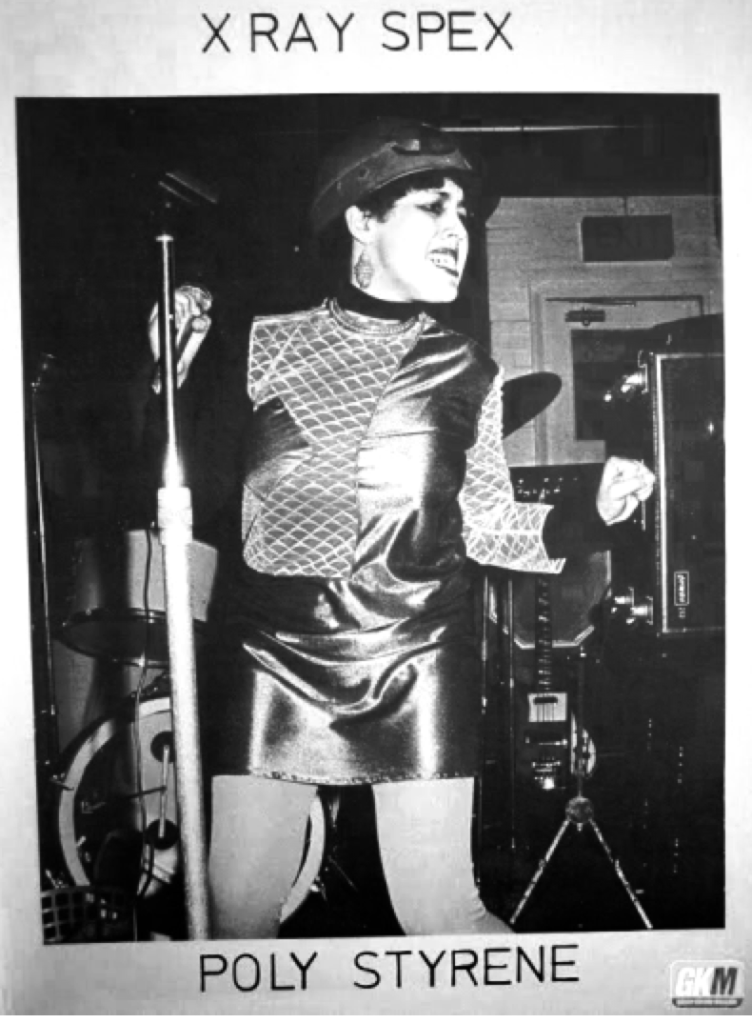

An explosion of aggressive sound during the emergence of the punk subculture under Thatchers government with input from the angst of what some would describe as the ‘all the white boys club’ from the Sex Pistols, The Clash, and The Damned which was a symptom of the alienation and anti establishment the youth were experiencing nationwide. However this subculture carried messages and influences from many voices. Described as ‘effervescently discordant’ singer Poly Styrene of the X-ray Spex contributed a new sound of discord unto a largely white male dominated subculture of punk.

“Poly gave a voice to people like her—women, the disenfranchised, people of colour—growing up in a London that was blighted by discrimination” https://elephant.art/oh-bondage-up-yours/

Alongside acts such as basement 5 in the 1980s who spoke up against the struggle of migrants described as a radical reggae punk fusion band from London, founded in 1978. this was a way to subvert the socially assigned identities many migrants had gained and find unity with the working class youth who also rejected the idea of sitting back and accepting this mistreatment.

[1] There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack’: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Hutchinson, 1987. https://www.dawsonera.com/Shibboleth.sso/Login?entityID=https://idp.goldsmiths.ac.uk/idp/shibboleth&target=https://www.dawsonera.com/depp/shibboleth/ShibbolethLogin.html?dest=https://www.dawsonera.com/abstract/9780203995075.

[2]Panayi, Panikos. Immigration, Ethnicity, and Racism in Britain, 1815-1945. Manchester [England]: Manchester University Press, 1994.

[3] Eddie chambers Cultural Politics in the making of black Britain roots and culture

[4] Moliterno, Alessandro G. “What Riot? Punk Rock Politics, Fascism, and Rock Against Racism.” Last modified 2012, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/612/2/what-riot-punk-rock-politics-fascism-and-rock-against-racism

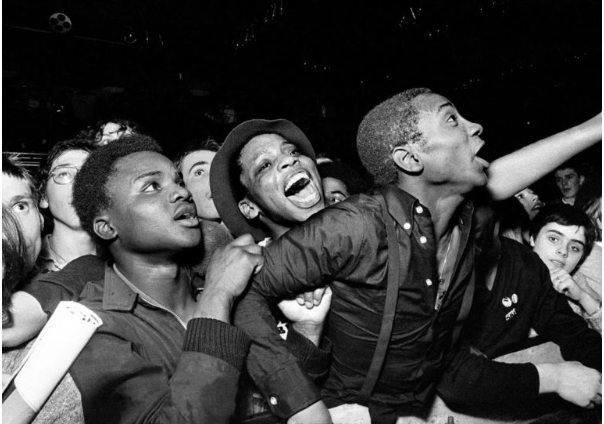

‘Punk was a refuge from racism. On the streets, young men like me were constantly getting pulled up by the cops. The far right were getting stronger throughout the 70s. But punk shows were bringing people together. The Clash were doing Rock Against Racism concerts. The Slits were doing gigs with Aswad. We were all cheering each other on. No racism in our bubble.’ https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/feb/22/this-much-i-know-don-letts-punk-music-dj-windrush#maincontent

DISCRIMINATION ON THE STREETS. Continuous harassment towards Black British youth from the police contributed to the need for a movement which contested this treatment that many were experiencing and the need to ‘articulate these experiences of struggle in song verse, and art.'[1] This necessity for expression meant that punk could be a welcoming scene to express this anger and give a direction to the disillusioned youth. Peter fryer explains how ‘these black men were subject to increasingly heavy handed policing – the police force was institutionally racist and deeply corrupt.’ [2] The punk subculture has been incredibly outspoken about its distinct dislike of the police force since its emergence in the 1970s and bands such as Sham 69 called for this anger to be directed toward police brutality rather than towards each other. With tracks such as ‘if the kids are united they will never be divided.’

‘the press covering them, heavily criticized the movement and its members as poseurs, fascists or communists, delinquents and so on.’ [3]

Unfair media portrayals furthered this alienation from British mainstream society. Black youth representation in media tabloid press were painted as the perpetrators of violence enabling the justification of heavy handed policing . Critiques of punk were plastered all over the press categorizing and demonising the subculture as a dangerous, radical movement which sought to undermine the government and the middle classes. Which in a way, it did. and that was exactly what was appealing about it for much of the youth who sought rebel and stand in defiance against the state Britain was in a that time. As a means to claim an identity and DIY style which distanced themselves from the status quo.

‘MY BLOOD BROTHER IS AN IMMIGRANT, A BEAUTIFUL IMMIGRANT.’

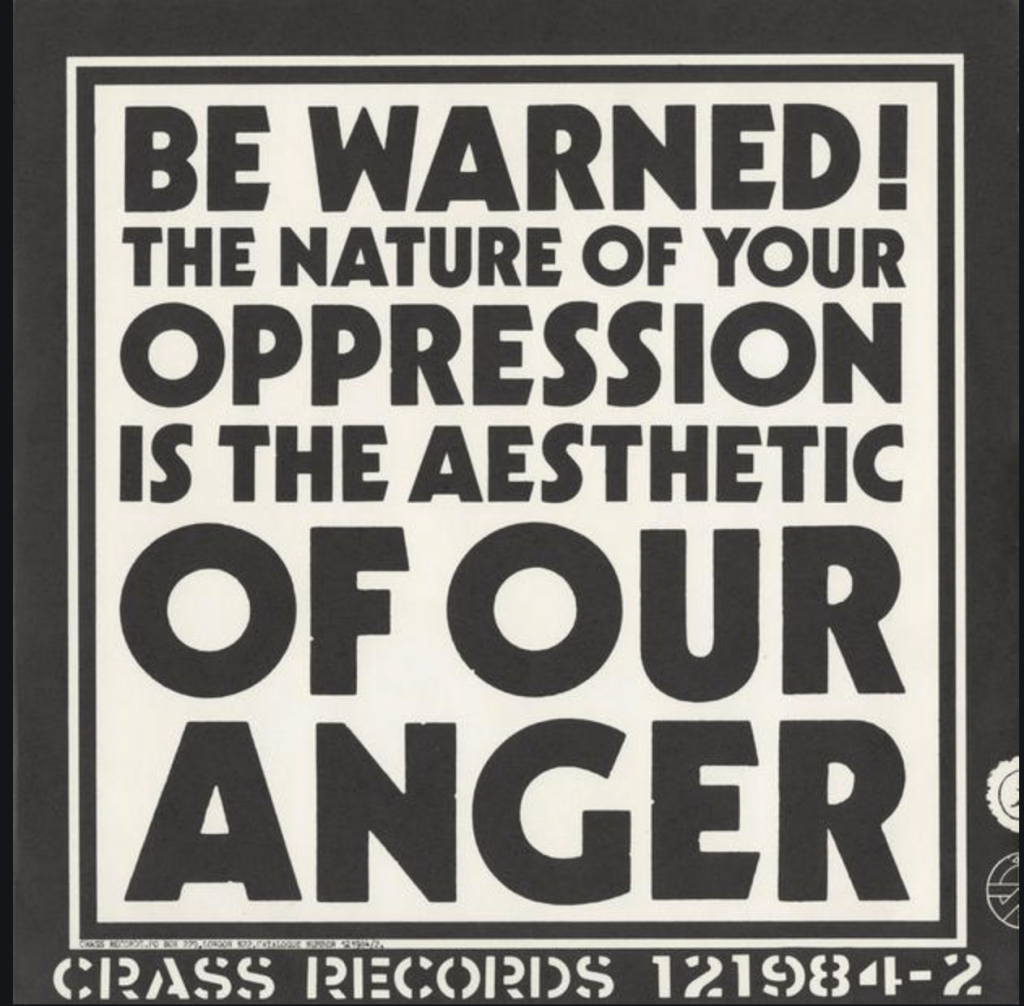

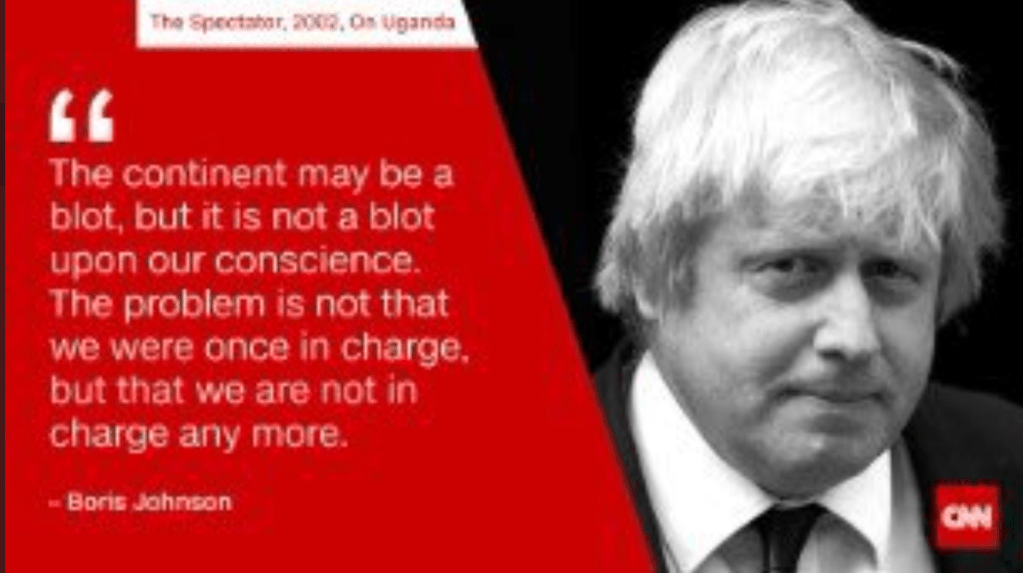

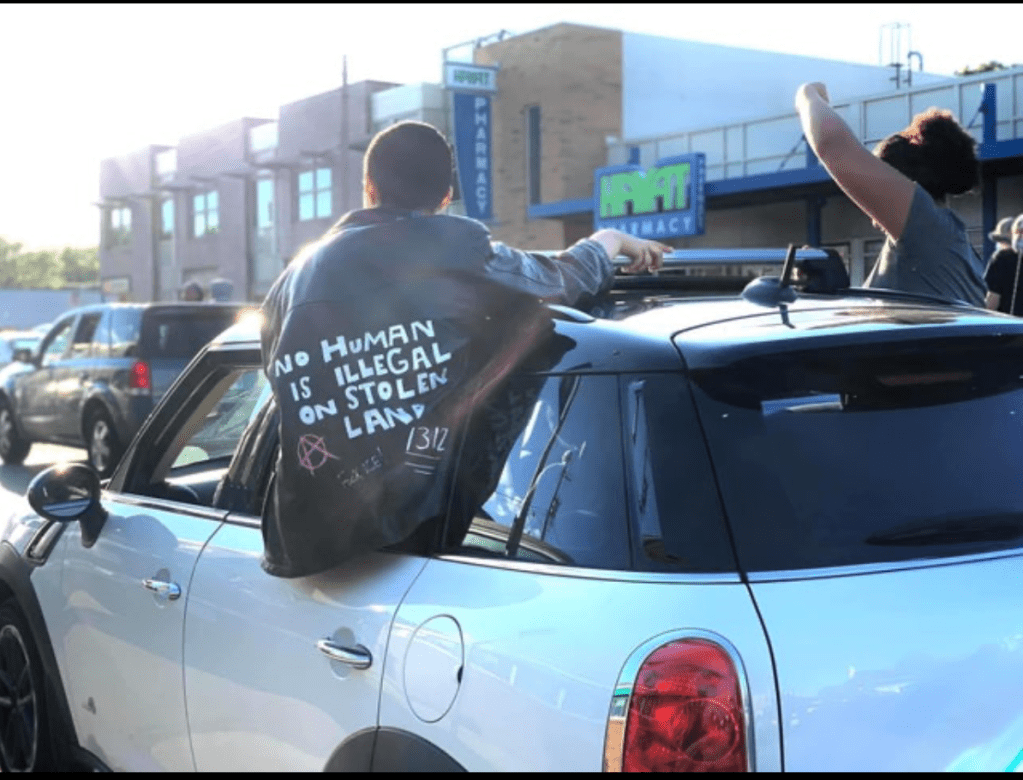

Today the punk movement has had a resurgence in recent years despite people saying the scene died a death. Artists have spoken out about the way Britain still has a long way to go in its attitudes toward race and immigration. The recent years have seen a revival of right leaning political movements such as UKIP. A Brexit campaign built upon tighter immigration controls. Post punk bands continue to use the sound and voice of punk to speak up against the continued discrimination happening in a deeply flawed and racist nation which continuously neglects fundamental issues within housing, healthcare, education and the prison system. UK racism not only exists today within micro-agressions nationwide. It has resurfaced in blatant and vicious ways . Through the use of the British Media , within Grenfell, in gentrification and stop and search policies. The sound of punk and its subculture is a vehicle for political change and activism, to give a voice to the continual injustice and to inspire unity and solidarity amongst the multi cultural society of Britain.

‘HE’S MADE OF BONES, HES MADE OF BLOOD, HES MADE OF FLESH, HES MADE OF LOVE, HE’S MADE OF YOU, HES MADE OF ME. UNITY.’ Joy as an act of resistance.

[1] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/goldsmiths/detail.action?docID=4791304.

[2] Fryer, Peter. Staying power, the history of black people in Britain. Pluto Press, 1984

[3] Moliterno, Alessandro G. “What Riot? Punk Rock Politics, Fascism, and Rock Against Racism.” Last modified 2012, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/612/2/what-riot-punk-rock-politics-fascism-and-rock-against-racism

‘Punk could be a blind, nihilistic rebellion, distinctly apolitical in its stance. At the same time there were fears that it would become oriented with the right, with neo-fascism and racism, or conversely that it had distinctly left-leaning tendencies.’ [1]

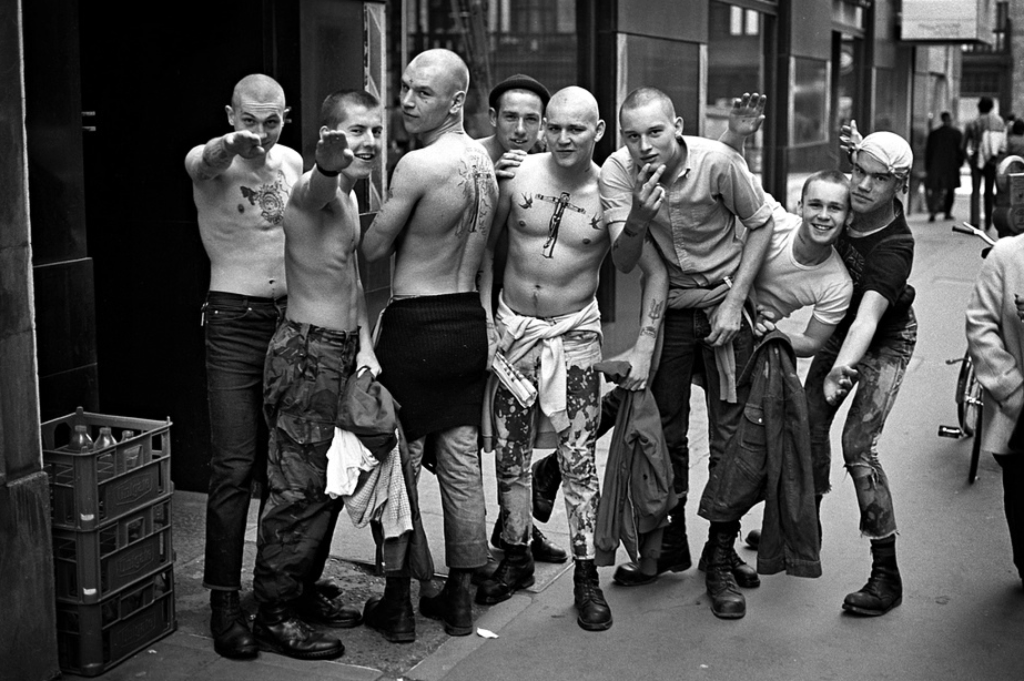

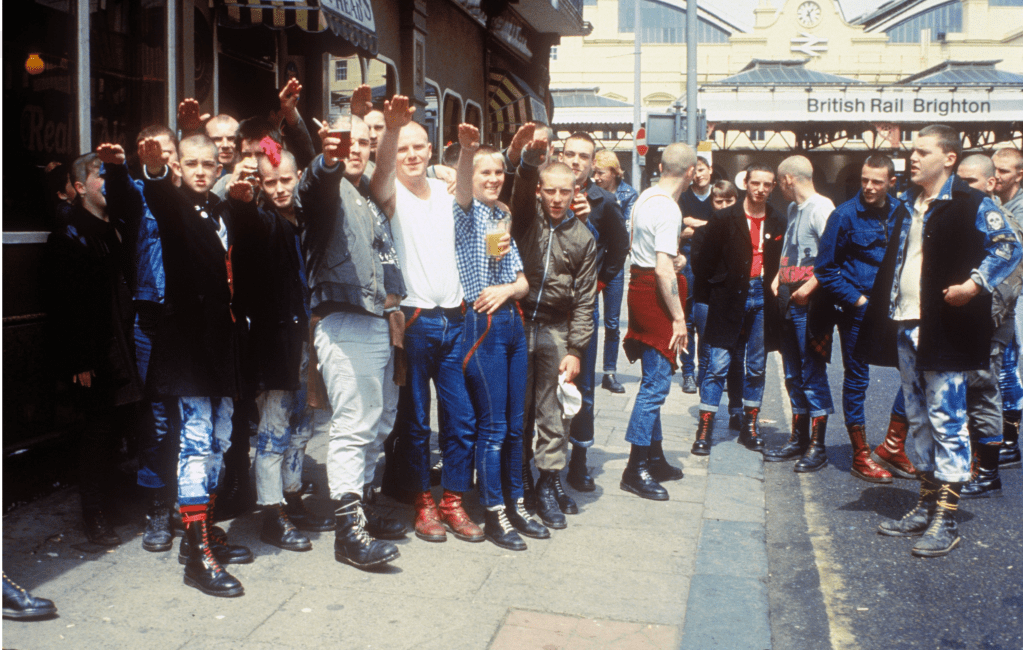

The punk and more notably the skinhead movement has received criticism over whether it was the unifying left leaning movement that people romanticise it to be. Despite the affirmation by many that it is an example of a successfully anti racist subculture it has had the issue of a culture gaining popularity and losing its way or being twisted to mean something else to fit individual movements agendas. An example of this is the skinhead movement which suffered greatly as a subculture through its affiliation with the national front and people who adopted it to push racist ideology. The growth of the far right and skinhead’s affiliation with the NF coincided with the time that governmental shifts were taking place to entice the right wing voters and when the movement did not gain traction and fizzled, conservative governments which were becoming increasingly discriminatory to encourage popular votes took its place. ‘This can be related directly to the issues resulting from the sense of political and economic crisis being faced more generally in Britain at the time, which incidentally can be seen as having contributed to a growth in racist rhetoric on the political scene. ‘ [2] Anger was redirected by the government and pointed the finger at migration to excuse the pitiful state of employment within Britain at the time rather than accepting responsibility that it was factory closures done by them that had created the problem. people were angry at the state of the economy and with a government that wouldn’t accept responsibility for that, the national front agenda and other far right movements were able to redirect this malleable anger and attract misguided youth to the cause. The alienated white youth were an easy target for exploitation and the ska movement suffered greatly with this. A stark contrast soon developed from the original scene where the working classes of all race were once united in a love for the music and style the culture once promoted.

‘ it is neither admirable nor astonishing that youths, even those involved in punk, who had grown up in the same neighborhoods, where the NF had been able to drum up support in the preceding years, might have held views that were xenophobic.'[3]

There are also critiques regarding the tendency for what some see as cultural appropriation within punk, where imported styles from countries were used with little understanding of the roots and meanings as it was fuel for the latest fad and it was seen as trendy and cool. The adoption of black music as well does not always equal acceptance and a good example of this is how although many racist/ neo-fascist skinheads would dance to reggae and sing the songs, their anger was directed at migrants rather than the side of skinhead which was all about unity and defiance against the oppression of racism and the understanding of the roots of the identity. The often violent expressions of nationalism and anti-immigration sentiments could not be a more dividing environment birthed from the punk music and ska scene proving that the kids could in fact be divided after all.

‘Influences from black culture were appropriated by working class youths during leisure time as material to fuel their youthful rebellion, but this did not mean that they shared affinity with their new neighbour’ [4]

[1] Moliterno, Alessandro G. “What Riot? Punk Rock Politics, Fascism, and Rock Against Racism.” Last modified 2012, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/612/2/what-riot-punk-rock-politics-fascism-and-rock-against-racism

[2] Moliterno, Alessandro G. “What Riot? Punk Rock Politics, Fascism, and Rock Against Racism.”

[3] Moliterno, Alessandro G. “What Riot? Punk Rock Politics, Fascism, and Rock Against Racism.”

Led Zeppelin post:

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Led-Zeppelin

Queen/Mercury post:

Queen

https://chartmasters.org/2020/01/queen-albums-and-songs-sales/

https://www.bl.uk/windrush/articles/calypso-and-the-birth-of-british-black-music

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C15734168

Iron Maiden post:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z6grnrd

https://www.cheatsheet.com/entertainment/iron-maiden-net-worth.html/

https://www.kerrang.com/features/the-unsung-influence-of-poetry-on-iron-maiden/

Anti-Racism post:

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-unoriginal-originality-of-led-zeppelin

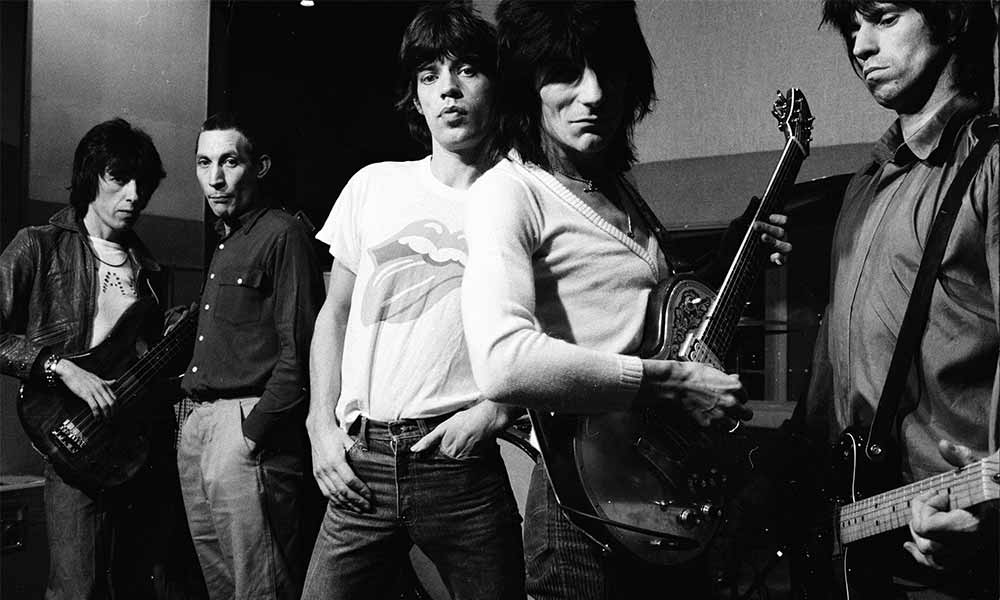

One of the main problems the black population faced in Britain after they immigrated was the widespread xenophobia and racism that were exhibited against them, which materialised through various musical acts, such as the very popular minstrel shows. It is safe to say that racism in popular culture was very prominent which is why the emergence of acts such as the Rolling Stones and other rock acts taking a stance against it

Rock music has had its beginnings from the black community stemming from bluesy musical forms evolving and many African American performers such as Chuck Berry or Jimi Hendrix embodied such developments. However, when we think of rock, we rarely associate it with black culture, which is why it has been often dubbed as cultural appropriation by white people. Although this can be debated, it is undeniable that black people have been excluded from rock music in popular culture.

Whilst there had been black presence in music for a long time, it was only during the 19th and 20th centuries that they really became popular. One of the biggest examples of this is the post-war emergence of calypso music, stemming from Caribbean such as Trinidadian folk.

Everyone has at least heard of the Rolling Stones, the rock band formed in London in 1962 by their original line-up, among them the legendary Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. One of the most legendary and successful rock band ever who embody the idea of what Rock n’ Roll was all about. A band from London that not only didn’t “appropriate”, but embrace their black influences and were noted how such successes were due to the “band’s purported connection to blackness and racial transgression, both in a musical sense and a more vague, imaginative one”.[1] This is not only a major step towards acknowledgement of black music, but also moved from cultural appropriation towards a sort of cultural appreciation. Something unfortunately not every band at the time were known for, such as Led Zeppelin who were often criticised for ‘stealing’ musical ideas from other artists.[2]

Such steps against racism were widely embraced by the 70s and 80s, which manifested itself in the creation of the Rock Against Racism and Anti-Nazi league movements, which ironically began with another famous rocker, Eric Clapton. During a 1976 concert Clapton shared his racist views with the audience which led to the immediate formation of the Rock Against Racism movement by Red Saunders, former Clapton fan.[3] Thus began a change in the appreciation of black culture in rock music, although to what extent this has succeeded is debatable.

[1] https://slate.com/culture/2016/10/race-rock-and-the-rolling-stones-how-the-rock-and-roll-became-white.html

[2] https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-unoriginal-originality-of-led-zeppelin

Self-expression through music is I believe the sharpest, most direct way a person can take to establish a sort of identity which was actually very common among the immigrants of the 20th century Britain. Music was a way to form a voice which was supressed by the government, for example people such as Lord Kitchener or Lord Shawty.[1] The resulting explosion of Caribbean, mainly Jamaican and Trinidadian music styles then formed many modern-day styles.

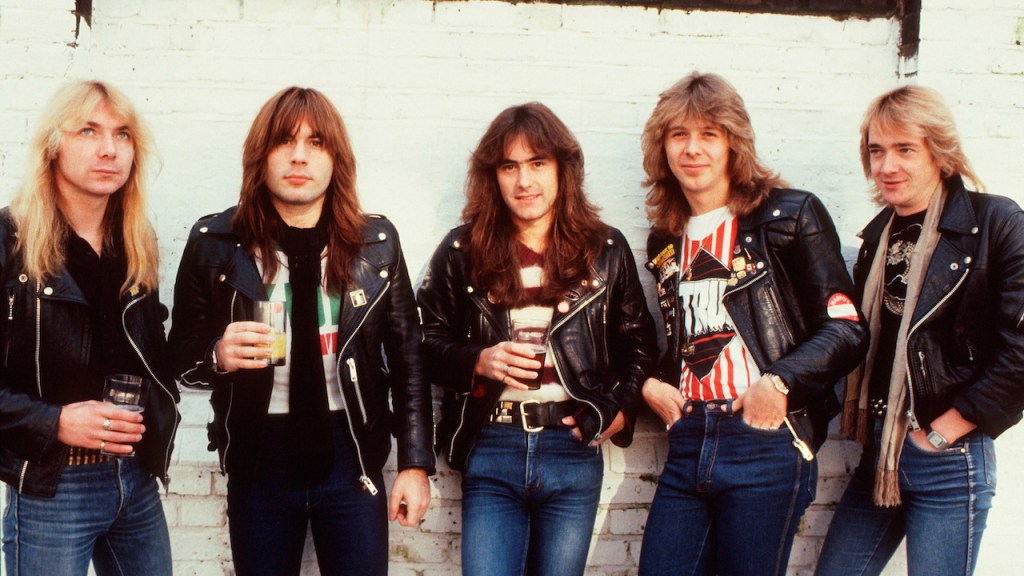

Iron Maiden is among my personal favourite musical acts of all time due to their vibrant and energetic live performances, poetry and other literature stuffed music, and unapologetically heavy metal sound. The band was formed in Leyton, East London in 1975 by Bassist Steve Harris and have since become one of the most recognisable, prestigious, and successful heavy metal bands in history with an estimated 100 million worldwide album sales.[2]

One of the most interesting things about iron maiden is their heavy influence from history and literature, something no everyday person would suspect of a bunch of ‘satan worshipping metalheads’, or so did the public would have thought. In fact, most of Iron Maiden’s catalogue is some form of re-telling of various historical stories (e.g.: Second World War) and literature (e.g.: The Rime of the Ancient Mariner). The latter is an exceptional piece of poetry which was reiterated in the form of a 13-minute-long epic under the same name on the 1984 album Powerslave.[3]

When we associate self-expression with music, Maiden cannot be excluded. As stated, “Steve Harris penned the song, changing the perspective of the original poem from first to third person, but keeping the horror and vision of Coleridge’s epic”.[4]

Iron Maiden’s reimagining of literary classics such as Coleridge’s poem shows how you can be influenced by something whilst adding a little bit of yourself into the mix. Not only does Iron Maiden help bring literature to the masses but teaches history in a similar fashion. A notable example is an equally amazing musical composition titled Alexander the Great which follows the life and achievements of Alexander the Great. There is a clear mixture of history and culture in Iron Maiden’s music which combined with the unique sound of heavy metal makes for an epic eye-opening experience on certain themes you otherwise might have overlooked.

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/articles/z6grnrd

[2] https://www.cheatsheet.com/entertainment/iron-maiden-net-worth.html/

[3] https://www.kerrang.com/features/the-unsung-influence-of-poetry-on-iron-maiden/

[4] Ibid

Queen is an English Rock Band which was formed in 1970 by singer Freddie Mercury, guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor, stemming from the latter two’s previous band Smile. Queen was (and is) among the most well-known and recognisable musical acts during the 20th century landing them worldwide success and fame.[1] With over more than 95 million record sales up to today, Queen has proven to be a universal musical influence for many a generations.[2]

Perhaps the most striking revelation about queen that people often overlook is the Far-Eastern/Asian influences that were present in the band’s image and music, starting with signer Freddie Mercury himself, who was of Asian origins. Mercury was born in Zanzibar and grew up in India until his family migrated to England in the 1960s at his age of just 17.

One of the biggest features of rock and roll is the freedom of self-expression and identity formation, mostly due to its rather rebellious nature. Thus, Queen’s superstardom is undoubtedly a source of inspiration for many minority groups given Mercury’s own personal background. Mercury’s also been cited as a universal influence due to his charming personality and unmatched vocal abilities which have guided a plethora of modern artists across various genres ranging anywhere between Lady Gaga or Katy Perry to the Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl implicitly influencing the music that reaches Millions, if not Billions of music fans around the world.[3]

During the mid-20th century there has been an explosion in immigration to Great Britain as personified by the period of Windrush through people seeking a better life for themselves which musically diversified England. Whether it be Calypso or Rock and Roll, music was a universal tool which minority groups have used to express themselves in.[4] Linking back to Mercury and his earlier mentioned life, his family fled Zanzibar from a revolution and moved to England in the mid ‘60s for a better life. As until 1963 Zanzibar was a British Protectorate, Mercury was what they called a ‘subject’ of the British Empire and applied for British citizenship after his relocation to England.[5]

Conclusively, Queen/Freddie Mercury’s musical success was one of many of the copious amounts of contributions immigrant groups brought to Great Britain and London. Although people tend to overlook the influences behind music such as Queen’s, there is undoubtable origins from overseas, that British Rock and Metal music could thank their existence for.

[1] https://history-biography.com/history-of-queen/

[2] https://chartmasters.org/2020/01/queen-albums-and-songs-sales/

[3] https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/pride/8483624/freddie-mercury-music-legacy-lady-gaga-brendon-urie

[4] https://www.bl.uk/windrush/articles/calypso-and-the-birth-of-british-black-music

[5] https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C15734168

Carter, Bob. Realism and Racism: Concepts of Race in Sociological Research. London: Routledge, 2000.

Gilroy, Paul. There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The cultural politics of race and nation. London: Routledge, 2002.

Goodyer, Ian. “Rock Against Racism: Multiculturalism and Political Mobilization, 1976-81,” Immigrants & Minorities 22:1: 44-62.

Habekost, Christian. Verbal Riddim: The Politics and Aesthetics of African-Caribbean Dub Poetry. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1993.

Heathcott, Joseph. “Urban Spaces and Working-Class Expressions across the Black Atlantic: Tracing routes of Ska,” Radical History Review No 87 (2003): 183 – 206

Herbert, Trevor. “The British Brass Band: A Musical and social History,” Music & Letters Vol. 82, No.2, ed. Philip Wilby 328-330. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Higgs, Michael. “From the street to the state: making anti-fascism anti-racist in 1970s Britain,” Race and Class Vol 58 No 1 (July 1 2016): 66-84.

Jeffries, Stuart. “ ‘Swamped’ and ‘riddled’: the toxic words that wreck public discourse” Last modified 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/oct/27/swamped-and-riddled-toxic-phrases-wreck-politics-immigration-michael-fallon

Mead, Matthew. “Empire Windrush: The cultural memory of an imaginary arrival” Journal of Postcolonial Writing 45:2 (2009) 137-149

Moliterno, Alessandro G. “What Riot? Punk Rock Politics, Fascism, and Rock Against Racism.” Last modified 2012, http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/612/2/what-riot-punk-rock-politics-fascism-and-rock-against-racism

Stratton, Jon. “Skin deep: ska and reggae on the racial faultline in Britain, 1968-1981,” Popular Music History Vol 5 No 2 (21 Nov 2011): 192- 215.

Sivananden, A. A different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance. London: Pluto Press, 1982.

Stuart, Andrea. “Riddym Ravings,” Marxism Today (November 1998): 44-45

Toynbee, Jason. “Race, History and Black British Jazz,” Black Music Research Journal Vol 33 No 1 (Spring 2013): 1-25

Olusoga, David. Black and British. London: Macmillan, 2016.