‘The Caribbean has long since been a region with a surfeit of labour, and consequently a region from which labour has been exported.’ [1]

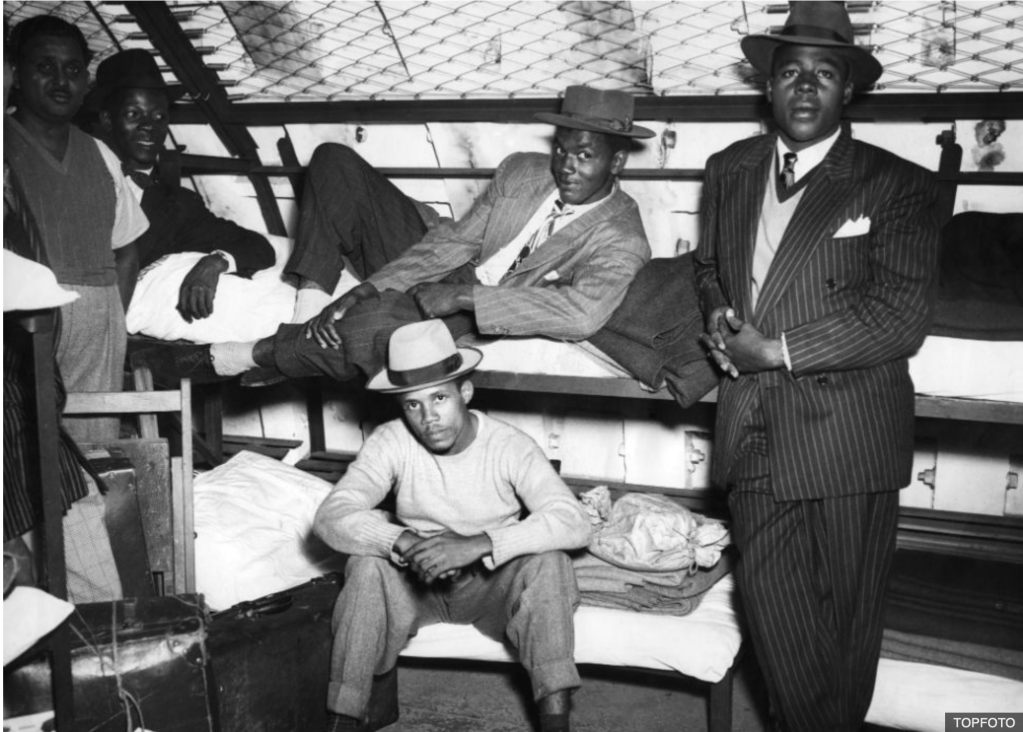

Wind rush was the largest scale of migration after world war two. There were various push and pull factors that bought people to Britain as the newly independent colonies found themselves in a state of impoverishment after years of exploitation through colonial rule from the British.[2] As well as the destruction reaped through natural disasters in Jamaica such as Hurricane Charlie. Britain, in contrast, had emerged victorious from world war two. The British economy needed rebuilding, fast. There weren’t enough British men in factories and public services and so Britain turned to its subjects overseas as they soon realised that due to its severe economic depression, places like the Caribbean could again be exploited.

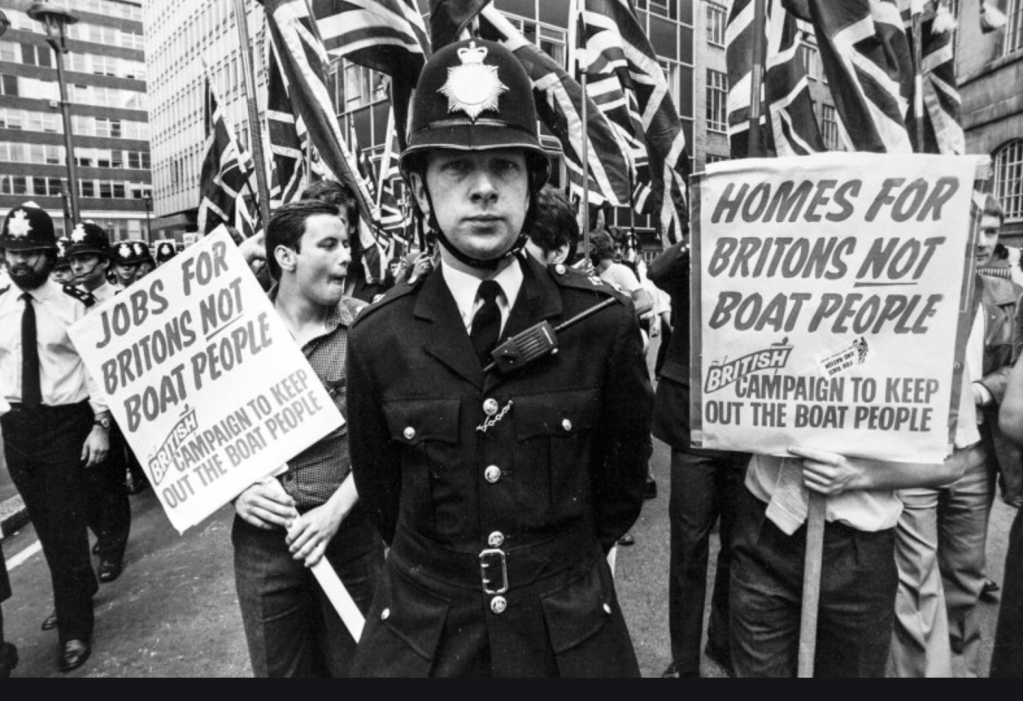

As British legislation had also been updated to allow this migration, the 1948 nationality act formally giving British subjects the new status of ‘commonwealth’ citizen. People of the commonwealth had been taught to retain a sense of pride and affection for mother country of Britain. [3] However, upon arrival they were continuously alienated through overt and covert racism and continuously let down by the British government and with the popular culture of Britain. These experiences of alienation from the ‘mother country’ and severed ties to cultures back home and continued hostility from the British public led to the disillusionment the migrants experienced when stepping foot on British land, experiencing hostility and alienation from a nation which they were both a part of and had contributed to throughout history.

‘these migrants found themselves not being treated as fellow brits, but as sinister foreigners’ [4]

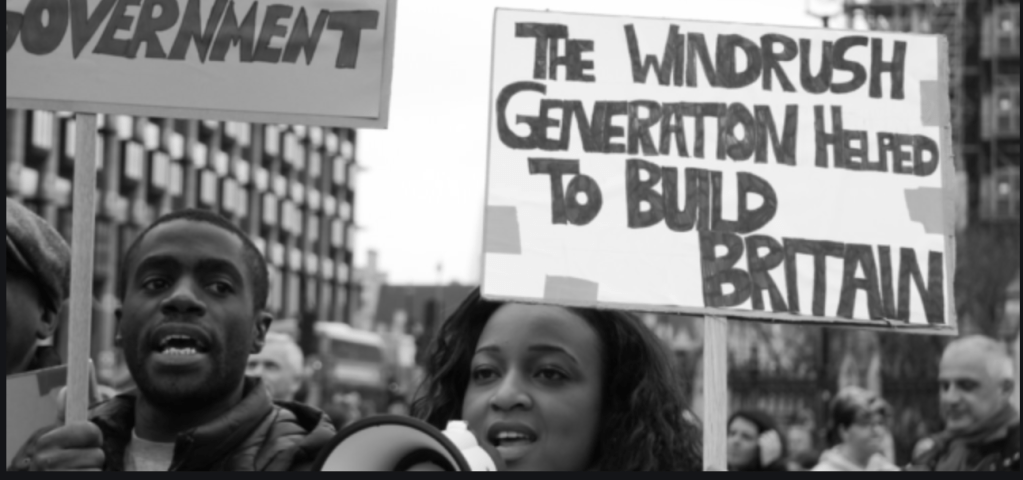

A blatant ‘demonisation of immigrant and foreigners was to become a perennial feature of public and political discourse.’ [5] Support for migrants was nowhere to be found within the systematic racism which existed in Britain and so during this time it had to come from their own local organisations and communities. Creating an environment where communities of migrants became insular and further alienated from mainstream British popular culture. The fact that Britain was completely ignorant to the cultural heritage, history, geography led immigrants a need to retain a sense of cultural identity as well as assimilating themselves into British culture. Especially by the second generation of wind rush. [6] These people had been completely cut off from the culture of their homes as their stay in Britain became more permanent and legislation prevented further migration. ‘Those Caribbean people already resident in Britain found themselves.. cut off quite literally from family and friends in Caribbean.’ [7] They therefore had to build something for themselves in the hostile landscape of Britain and music was a way in which to do this. Migrants found themselves in a state of constant resistance to British people socially assigning identities to migrants and the ‘lumping together’ of cultural heritage. [8] And so as Paul Gilroy states in his work on cultural politics of race and nation, ‘recognition of the ways in which Britons black populations are subject to particularly intense forms of disadvantage and exploitation.’ [9] There was a distinct need to express this struggle within the forms of music and art to form a collective identity against this systematic oppression.

The children of Windrush sought to claim a distinctive black-british cultural identity and it began to emerge as migrants looked toward black conciousness and political movements flourishing in the States. Music was a crucial way in which black British youth could express this rejection of their discrimination. The disappointment and anger toward a government who had completely failed them and their parents before them and the lack of affinity they felt with the people of Britain. In the following posts I will explore how music was a key defining feature in this development of identity and how it transformed the punk and ska scenes over the decades.

‘Since the end of the world war millions of migrants and their offspring have helped to revitalise and transform Britain.’ [10]

[1]Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/goldsmiths/detail.action?docID=4791304. p.29

[2] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.29

[3] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.27

[4] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.32

[5] Sivanandan, A. A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance. London: Pluto Press, 1982. p.35

[6]Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain. p.32

[7] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.42

[8] Chambers, Eddie. Roots and Culture : Cultural Politics in the Making of Black Britain, p.42

[9] There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack’: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Hutchinson, 1987. https://www.dawsonera.com/Shibboleth.sso/Login?entityID=https://idp.goldsmiths.ac.uk/idp/shibboleth&target=https://www.dawsonera.com/depp/shibboleth/ShibbolethLogin.html?dest=https://www.dawsonera.com/abstract/9780203995075. P.10

[10] Panayi, Panikos. Immigration, Ethnicity, and Racism in Britain, 1815-1945. Manchester [England]: Manchester University Press, 1994.